Puppet mastered

Puppet mastered

Puppet mastered

November 30, 2021 5:35 pm

Critic After Dark

Noel Vera

Movie Review

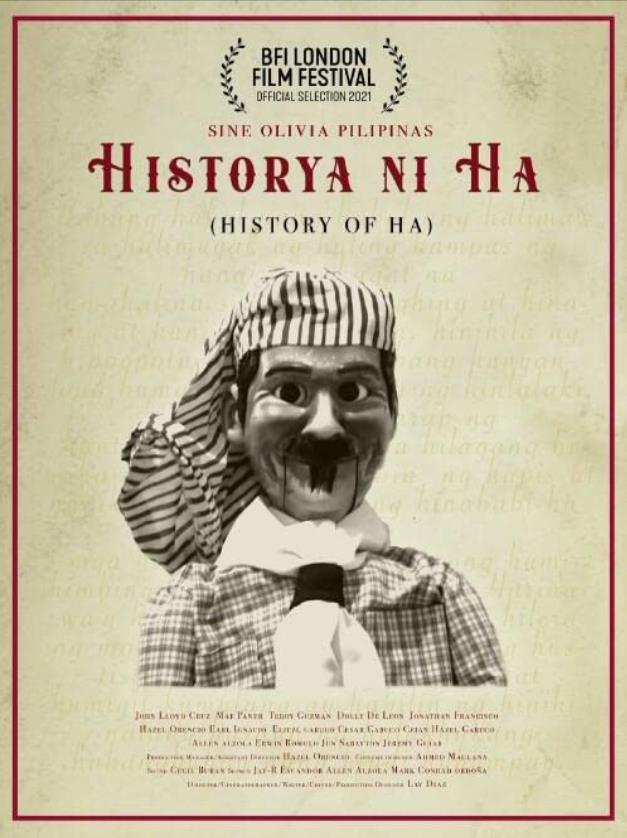

Historya ni Ha

Directed by Lav Diaz

Lav Diaz’s

Historya ni Ha

(

History of Ha

) may be his strangest work yet. If in

Ang Hupa

(

The Halt

, 2019) he proposes a Filipino dystopia complete with dictatorship and pandemic and volcano-induced darkness, and in

Panahon ng Halimaw

(

Season of the Devil

, 2018) he presents the Philippines’ first-ever black-and-white, sung-through, no-instrument musical, this you might say is his

Dead of Night

– an astringently deadpan blackly comic film about a ventriloquist and his dummy.

Hernando Alamada (John Lloyd Cruz) is a former Huk insurgent turned famed

bodabil

star, performing for passengers on the

Mayflower

as it sails international waters. It’s his last tour; he plans to take his savings to his hometown and marry his childhood sweetheart Rosetta – only it’s not to be: Rosetta has promised herself to a rich man, to pay off family debts. Hernando goes into self-exile instead, and the story proper begins.

We’ve seen this figure before in Diaz’s films, from his earliest (

Burger Boys

, 1999 – first to production, second released) to

Kriminal ng Baryo Concepcion

(

Criminal of Barrio Concepcion

, 1998) to

Batang West Side

(

West Side Avenue

,

2001) to

Ebolusyon ng Isang Pamilyang Pilipino

(

Evolution of a Filipino Family,

2004) to as late as

Panahon ng Halimaw

– the loner wanderer, sometimes the film’s ideological torchbearer, sometimes its heart of darkness.

One wonders if this figure actually exists in Diaz’s life, though one would be hard pressed to guess who – his father? Diaz himself? In

Burger Boys

he’s a haunting haunted figure in one boy’s life, the father he wished he could have loved but never quite knew, represented by a wood angel statue his father once carved but was unable to finish – the statue stands by a roadside, its arms ending in stumps. In

Ebolusyon ng Isang Pamilyang Pilipino

he’s Raynaldo (Elryan de Vera), a boy who wanders from town to town, family to family, fate uncertain, belonging to none, less protagonist than mute witness to the random currents of history. In

Batang West Side

he’s two figures: young Hanzel Harana (Yul Servo), who moves from the care of mother to grandfather to the tutelage/patronage of a malevolent (if irrepressibly funny) drug lord, eventually walking the Jersey streets straight into a bullet; he’s also Detective Juan Mijares of the NJPD (Joel Torre), an insomniac introvert of a police officer who grapples with the unpromising investigation of Hanzel’s death and his own personal demons.

The eponymous hero (Mark Anthony Fernandez) of

Hesus Rebolusyonaryo

(

Jesus Revolutionary

), Hugo Haniway (Piolo Pascual) of

Panahon ng Halimaw

, and Hook Trollo (Pascual again) of

Ang Hupa

are slightly different: former revolutionaries and artists forced by circumstance to retire or go into hiding, then forced by circumstance

again

to confront their anguished past. Hernando is more recognizably in this category, though his chosen profession – ventriloquism – seems an odd choice till you think about it: vaudeville (or

bodabil

as colloquially known) was a popular artform in the 1950s, Diaz’s chosen time period; the ventriloquist was an established member of the vaudeville troupe. One may wonder if a Filipino ventriloquist can ever achieve nationwide recognition until one remembers Manuel Conde who started out as a ventriloquist, and some of whose early films featured performances with his puppet Kiko (the prints now lost, alas).

So this figure steps out from among a gallery of familiar figures inhabiting Diaz’s films, practicing a period-accurate profession while enjoying period-accurate (somewhat) level of fame – but the period is crucial to Diaz’s thesis, and so (I submit) is the nature of his lead character’s profession.

It’s 1957, and President Ramon Magsaysay has just been killed in a plane crash; journalist Jack Agawin (Erwin Romulo) is picking apart the late president’s legacy: “this cycle of mythmaking,” he darkly prophecies, “will keep on repeating here in the Philippines,” such that “the masses will vote false prophets and leaders.” Later one such leader, Among Kuyang (Teroy Guzman), will echo Agawin’s prediction with his own forecast: “Two decades from now we will have a leader from the North… six decades from now a leader from the South.” He adds with relish: “I like them a lot.”

Diaz puts a finger on one big reason why the Philippine electorate time and time again makes poor choices: they’re in love with the idea of the savior-superman, a leader that will rise up and solve all our problems with a Presidential Decree or two. Agawin’s analysis is (as Congressman Torres [Jun Sabayton] puts it) “quite horrifying” if baldly stated, but, as in the best vaudeville magic, the obvious gesture is meant to distract the audience while the hidden hand performs the real trick: Hernando sitting in one corner drinking in Agawin’s postmortem and Among Kuyang’s forecast. One almost feels Hernando is reacting to this the same way he reacts to Rosetta’s rejection: with silence. In the face of such insanity (a presidential myth perpetuating two other myths, a woman giving herself up for her family’s debts) what else can one say?

Which is where Ha (acronym of Hernando’s name, presumably) comes in. Most films involving ventriloquists (

Magic

,

Dead of Night

) have the dummy manifesting the performer’s id, saying things he wishes he could say, uttering thoughts that would be unspeakable in polite company but hilarious from a wooden mouth. Difference is that in those films the issues are personal while Ha talks of the grievous hurt of the world, in the form of jokes and poems. “How about you Hernando my friend?” Congressman Torres asks, “What’s your point of view?” Hernando pauses a beat: “I will have to talk to Ha.” Even this early Hernando is smart enough to use Ha as a way to express or obscure what he wants to say.

Ha isn’t the kind of troublemaker Hugo or Fats is; if he lectures us on politics or the failures of human nature his lectures are softened with humor, couched in rhyme; he’s open and direct only with Hernando, in their long conversations together – first time in a field, where they talk over options and Hernando’s motives; later in the bathroom, when they discuss what to perform for their comeback show. Ha is sly, funny, sometimes cruel: “Loser,” he calls Hernando, for letting Rosetta’s decision get him down; their conversations together have the intimacy of longtime friends who don’t necessarily like each other but know each other too well (that Lloyd Cruz can do both sides of the conversation and that we accept this without much trouble says something of his acting skill).

Hernando and Ha’s second long conversation takes place in the toilet, in front of a mirror, and eventually you realize that Hernando is talking to Ha, who’s perched on a windowsill to his left, at the same time he’s staring at himself in a mirror. Ha’s words here are even more cutting: the masses “are on the level of animals,” and he gleefully declares that they might as well dance with the devil. Lloyd Cruz plays a complicated game, peering over his shoulder when he wants to address Ha; when Ha speaks the voice sounds as if it’s coming from out of the glass.

Visually speaking Diaz continues to make the ironic point that the rural Philippine landscape is breathtaking to behold, all towering screens of bamboo, broad canopies of

narra

and mango leaves, endless grassland – that folks could suffer crushing poverty in the midst of all that beauty is a maddening mad-inducing paradox. Early on, Hernando receives a letter from Rosetta that starts loving and turns out to be a tearful farewell; as Hernando sits digesting this mortal gut punch, Diaz has the sun pierce through a passing cloud and set the world on fire. Later, what is arguably the film’s most painful moment also happens to be its most beautiful: Hernando standing hip-deep in seawater with Ha while the moon glares down from high overhead, the belly of storm clouds crackling with thunder to the distant left. With each film and with his low-budget high-definition digital camera, Diaz only seems to grow as a filmmaker.

I talk at length of the wanderers that walk through Diaz’ films and for a reason: I see them as iterations of Diaz himself, walking through each film and its unique challenges and posing to himself (and through him, us) the question: how would you feel? What would you do? And why? Diaz proposes yet another set of answers to the questions, different from his previous responses: not perhaps as ambiguous (though breathlessly timed) as in

Panahon ng Halimaw

, and not perhaps as quietly hopeful as in

Ang Hupa

. He has three men digging a hole in the ground, and the image suggests several implications: that of three men excavating a grave, presumably for Hernando’s previous hopes and dreams; that of a new building’s foundations mentioned in Hernando’s letter, a symbol of his present aspirations; and that of a latrine, a receptacle for human shit, which in fact is what the three are digging. Diaz leaves the image there for us to gaze at, pick which option suits our temperament, maybe come up with new possibilities of our own – a Rorschach test we can project our hopes and fears on till the next time he presents a new set of questions.

Historya ni Ha

is one of the films being shown in the ongoing QCinema film festival. This year, QCinema is a hybrid festival with both on-site and online screenings. It is ongoing until

Dec. 5, with theatrical screenings at the Gateway Cineplex 10 in Quezon City, and online streaming via KTX.ph.