PHL up a spot in corruption index but score remains low

Kyle Aristophere T. Atienza, Reporter

THE PHILIPPINES saw its ranking improve one spot in a global corruption index by watchdog Transparency International, although its score remained at record low.

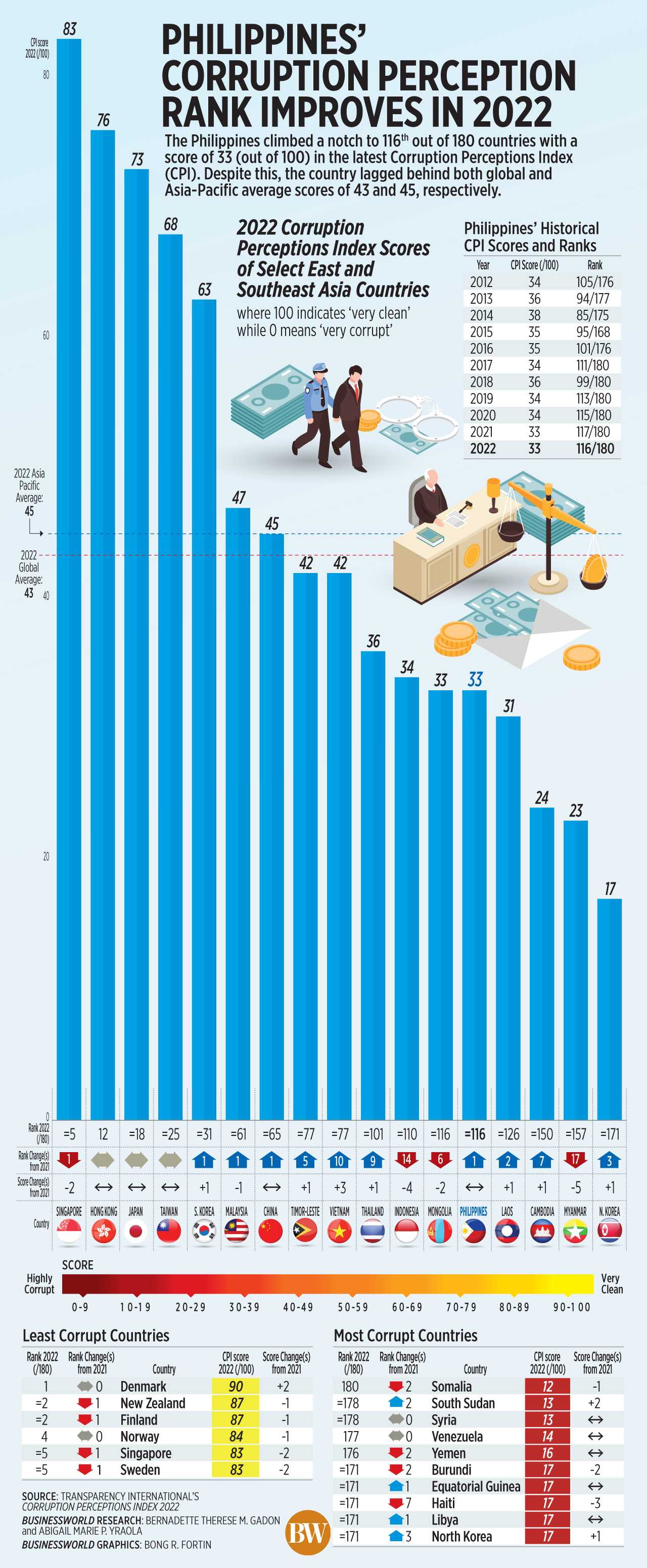

Based on the 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), Manila ranked 116th out of 180 countries, up one spot from its worst-ever showing of 117th place in the previous year. The Philippines ranked 115th in 2020, 113th in 2019, and 99th in 2018.

However, the country’s score was unchanged at 33 out of 100 in a scale that measures perceived levels of public sector corruption. A score of 100 means a country is “very clean,” while zero means it is “highly corrupt.”

The Philippines’ latest score is also below the global average of 43 and Asia-Pacific region’s average of 45.

“Asia-Pacific continues to stagnate for the fourth year in a row with an average score of 45 points. While some governments have made headway against petty corruption, grand corruption remains common. Pacific leaders have renewed focus on anti-corruption efforts, but in Asia, they have focused on economic recovery at the expense of other priorities,” Transparency International said in its report.

In a bid to consolidate power, Transparency International said regimes in the region have been curtailing space for dissent through “draconian” laws that restrict free speech. It also cited a “worrisome” trend toward authoritarianism as governments maintained — and in some cases expanded — restrictions on civic space and basic freedoms imposed during the pandemic.

“Democracy has been declining in the region, including in some of the most populous countries in the world, such as India (40), the Philippines (33) and Bangladesh (25),” it said.

Among Asia-Pacific countries, the Philippines lagged behind Singapore (5th), Hong Kong (12th), Japan (18th), Taiwan (25th), South Korea (31st), Malaysia (61st), and China (65th). It was also behind Timor-Leste (77th), Vietnam (77th), Thailand (101st), and Indonesia (110th).

The Philippines was only ahead of Laos (126th), Cambodia (150th), Myanmar (157th), and North Korea (171st).

Denmark, which scored 90, topped the 2022 CPI, followed in second spot by Finland and New Zealand, which both scored 87.

At the bottom of the list were Somalia, Syria and South Sudan, which continued to be involved in a protracted conflict.

Nearly 90% of countries in the region “have made no significant progress” since 2017, Transparency International noted.

PATRONAGE POLITICS

“Corruption has been a trend not just in Asia but worldwide,” Hansley A. Juliano, a political economy researcher, said in a Facebook Messenger chat.

“What we are seeing here as well is an exposure of the significant weaknesses of democratic checks and balances and a disconnect between traditional ‘value holders’ of democratic politics and the larger population.”

In the Philippines, Mr. Juliano said patronage politics continue to worsen corruption, with citizens seeing the practicality of siding with politicians.

Opposition forces and other anti-corruption advocates would have a hard time defeating corruption because for ordinary people, “the exchange of political support for tangible gains is ‘democratic enough,’” he added.

“The fact that we seem to have settled into primarily taking potshots at the Marcos administration’s blatant excesses, which do not translate to any form of public support decline, is already telling,” he said.

The inability to “genuinely normalize” support for institutional means of accountability, coupled with political disinformation, helps build “constituencies for draconian governments,” he added.

Emy Ruth D. Gianan, an economics professor at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP), said the Philippines’ low score in the corruption perceptions index “is a reminder that our political institutions remain untrustworthy for experts and investors.”

Ms. Gianan said via Messenger that the long-standing issue of corruption in the Philippines is worsened by the “poor regard for human rights and significant socioeconomic inequalities.”

Leonardo A. Lanzona, who teaches economics at the Ateneo de Manila University, said the prevalence of corruption against the backdrop of the country’s economic problems is worrisome.

“Aside from its impact on the macroeconomy, corruption can play a significant role in exacerbating labor market conditions and thus poverty,” he said via Messenger chat.

Corruption, Mr. Lanzona said, reduces the availability of public resources and social protection measures for low-skilled workers, making it harder for them to compete in the labor market and increasing their vulnerability to poverty and unemployment.

He noted the government failed to highlight the economic importance of anti-corruption efforts in the Philippine Development Plan for 2023 to 2028, which was approved by President Ferdinand R. Marcos, Jr.

“Given its enormous impact on developing and protecting the capabilities of individuals and families, the PDP 2023-2028 could have used corruption as a focal point for coordination and implementation.”

BLEAK OUTLOOK

Mr. Marcos earlier said foreign investors who want to do business in the Philippines are more concerned about high power costs and ease of doing business than they are about domestic transparency and accountability.

“Those who are actually contemplating putting good money in the Philippines have other issues. Accountability and transparency (are) not an issue,” he said.

Maria Ela L. Atienza, a political science professor at the University of the Philippines, said she believes there is no seriousness in the government’s anti-corruption campaign.

“Crony capitalism and patronage and traditional politics continue in the absence of weak political parties and with threatened civil society as well as a pressured justice system,” she said.

To boost anti-corruption efforts, the government needs to improve the credibility of independent political institutions and speed up the trials for high-profile graft and corruption cases, PUP’s Ms. Gianan said.

“Long-shot for us to regulate political dynasties and nepotism, but a serious public discourse on that may help shed light on potential solutions against the undue advantages of familial ties in politics.”